DISKURSER

Udgangspunktet for

diskursanalysen er, at det

samfund, vi

”ser for os”, er bestemt af det sprog, vi bruger om det. Diskurs er

sprogbrug

anvendt på samfundet. Samfundet eksisterer ikke i sig selv, kun igennem

vores iagttagelse

og den sprogbrug, iagttagelsen beskrives med. Verden dannes for os

igennem

sproget. Det er udgangspunktet for diskursanalysens måde at se verden

på.

Nogle

ord er abstrakte, f.eks.

”demokrati”. Nogle ord er konkrete, f.eks. stol. Vi kan se en konkret

stol og

flytte rundt med den. Vi kan ikke se noget konkret, der svarer til

begrebet

”demokrati”. Der er ikke her noget konkret, vi kan flytte rundt i

rummet. Men

vi kan påvirke andres demokratiholdninger via en diskurs om demokrati.

Vi

kan se en arbejdsløs person, men vi

ser kun personen som ”arbejdsløs”, når den sproglige etiket

”arbejdsløs” er

hæftet på personen. ”Arbejdsløshed” som begreb ser vi ikke. Det er jo

kun

”arbejdsløshed”, fordi vi bruger sproget på en bestemt måde. Den

”arbejdsløse”

er på en måde i arbejde/beskæftigelse, når vedkommende reparerer sin

motorcykel. Men det tæller ikke som arbejde i officiel

arbejdsmarkedsmæssig

forstand. Om personen ”arbejder” eller ”ikke-arbejder” bestemmes altså

sprogligt i diskursen.

”Arbejdsløshed” er det, man

kalder ”floating signifiers” (flydende bestemmere). Brugen afhænger af

den, der

bruger ordene, og af sammenhængen de bruges i. Ordet ”demokrati” blev

brugt på

en anden måde i et såkaldt ”Folkedemokrati” i Østeuropa før 1989, end

det

bliver brugt i Vesteuropa i dag.

I en diskurs lægger man sig

fast

på en bestemt måde at definere ordene og bruge sproget på. Det er man

nødt til,

fordi diskursen bruges til at kommunikere noget til andre eller påvirke

dem på

en bestemt måde. Den, der bestemmer diskursen kan komme til at bestemme

den

samfundsmæssige udvikling eller dele af den.

Man taler om en hegemonisk

diskurs som en diskurs, der har vundet herredømme (hegemoni =

herredømme).

Hvis

man f.eks. ser på diskurser om

arbejdsløshed, så vil nogle hæfte sig ved ”Dovne Robert” fænomenet, dvs

de

arbejdsløse gider ikke arbejde, mens andre vil se på, at de arbejdsløse

ikke

kan få et job, fordi den økonomiske aktivitet i samfundet ikke er stor

nok til,

at der er jobs til alle. Hvis den første diskurs vinder mere frem end

den

anden, kan det evt. bruges til at skære ned på

arbejdsløshedsdagpengene. Folk

vil forstå det, fordi de er mere påvirket af diskursen, der siger, at

de

”arbejdsløse driver den af”, end den, der siger, at de arbejdsløse er

”uden

skyld i, at der ikke er jobs at få”.

Vigtige ord i diskurser:

NØGLEORD

(nodalpunkter), som står i modsætning til

nøgleord i konkurrerende diskurser

FORBUNDNE LIGEVÆRDSORD

(ækvivalensbegreber/ækvivalenskæder), som

understøtter diskursen

MODSTÅENDE BEGREBSPAR AF INKLUSION/EKSKLUSION (”vi”/”dem”)

I diskurserne i boksen er de modsatstående nøgleord yde (= være i

arbejde) og

nyde (være arbejdsløs og på understøttelse/ kontanthjælp). Der er forbundne ord som

arbejde (det

modsatte af arbejdsløshed).

”Dovne

Robert” diskursen påvirker

holdningsmæssigt ved brugen af negative ækvivalensord som skod-arbejde,

samle

klemmer, pedel (nedværdigende betegnelse, jvf at McDonalds selv

betegner dem

som assistenter, partnere, interessenter, stjerner m.v.). Det siges

ikke

direkte, men de negative ord står som om, de

er citeret

fra Dovne Robert selv.

Det fremgår ikke, om han rent faktisk har sagt lige præcis sådan i

direkte

citat. Der stilles til sidst nogle retoriske spørgsmål, som ethvert

fornuftigt

tænkende menneske må kunne se det rigtige svar på. Men nej, det kan

Robert

ikke!

|

”Dovne

Robert” diskursen kontra ”De

arbejdsløse er til rådighed” diskursen Arbejdsløse

er til rådighed og vil gerne arbejde Foran

Jobcentret i Aabenraa var det dog en noget anden holdning der mødte os,

da vi kiggede forbi: -

Jeg har altid arbejdet, man skal arbejde for sine penge, helt klart.

Jeg har nogle handicaps der gør at jeg ikke kan klare hårdt fysisk

arbejde, men ellers skal man tage imod tilbud. Hvis man vil nyde noget,

må man også yde noget, siger han. Samme

holdning går igen hos 53-årige Peter Sørensen fra Jyndevad, der har

været arbejdsløs i cirka et år og nu er på dagpenge. Han er uddannet

mekaniker, men ville gerne tage imod et job, der for eksempel gik ud på

at brænde ukrudt væk fra fortorve - selvom det er under hans

uddannelsesniveau: -

Det er bedre at komme ud og møde mennesker end at gå hjemme og lave

ingenting. Sådan noget som handicaphjælper eller sundhedshjælper er jeg

nok ikke så god til, jeg vil hellere noget teknisk. Men jeg ville nok

prøve det, hvis jeg fik det tilbudt, siger han. (Kilde: Dr.dk 11.9.2012) |

I den anden tekst omtales

villigheden til at arbejde positivt som konkrete beskæftigelser.

Arbejdet - ja

endda en hvilken som helst form for arbejde - fremhæves som positivt af

arbejdsløse, som modsætning til ikke-arbejde, som er at gå hjemme og

”lave

ingenting”. Gennem denne modstilling af modsatte begrebspar omkring

arbejde-ikke-arbejde, og at det er arbejdsløse, der citeres, laves

meget mere

positiv diskurs om ledige. Vi kan nu ånde lettet op. Det er heldigvis

ikke alle

de arbejdsløse, der er som Robert.

Noget af de afgørende ved en diskurs er imidlertid ofte, hvad der ikke siges. Når man vælger en bestemt diskurs, har man jo fravalgt at sige andre ting. Det kunne jo f.eks. tænkes, at Dovne Robert var blevet træt af al medieomtalen og var begyndt at optræde som Rasmus Modsat. Hvis man anvendte en anden italesættelse af hans problemer over for ham, er det tænkeligt, at han ville reagere anderledes, - også diskursivt.

Moderne politikere lever i en politisk

virkelighed, hvor medierne ofte tvinger dem til at formulere sig i one-liners

(enkle, korte budskaber formuleret i få sætninger). Det er en af betingelserne

i den politikkens medialisering, vi lever i. En af de politikere, der har formuleret

en af de mest omdiskuterede one-liners i nyere tid, er den britiske

premierminister Margaret Thatcher (premierminister 1979-91). Det var hendes

bemærkning om samfundet: there is no such thing as society.

There are individual men and women.

Bemærkningen kan lægge op til mange fortolkninger, og det hænger

naturligvis sammen med, at ordet ”society” (samfund) i høj grad er det, man kalder a floating

signifier (”en flydende betegner”). Hun går ind og udlægger begrebet

diskursivt og siger, at når man har sagt, at ordet indebærer en opfattelse af

sammenhæng imellem samfundsborgerne, ja, ligefrem solidaritet, så siger hun, at

direkte oversat, vil hun forstå samfund som en samling af individer, hvor der

ikke er angivet noget om social sammenhæng og solidaritet imellem dem. Dermed

kan udsagnet udlægges som ultraliberalisme: Samfundet er en samling af

atomiserede individer, der ikke i sig selv behøver at være solidariske med

hinanden.

Men det er måske ikke lige det, hun har

ment, når sætningen sættes ind i den sammenhæng, ordene blev sagt i:

‘I

think we have gone through a period when too many children and people have been

given to understand “I have a problem, it is the Government’s job to cope with

it!” or “I have a problem, I will go and get a grant to cope with it!” “I am

homeless, the Government must house me!” and so they are casting their problems

on society and who is society? There is no such thing! There are individual men

and women and there are families and no government can do anything except

through people and people look to themselves first… There is no such thing as

society. There is living tapestry of men and women and people and the beauty of

that tapestry and the quality of our lives will depend upon how much each of us

is prepared to take responsibility for ourselves and each of us prepared to

turn round and help by our own efforts those who are unfortunate.’( http://blogs.spectator.co.uk/coffeehouse/2013/04/margaret-thatcher-in-quotes/)

Komplekse, abstrakte ord tager altså betydning af de sammenhænge, de optræder og bruges i.

Eks:

David Cameron

Downing Street 10

Statement on UK Riots 10 August 2011. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/crime/8693134/UK-riots-David-Camerons-statement-in-full.html

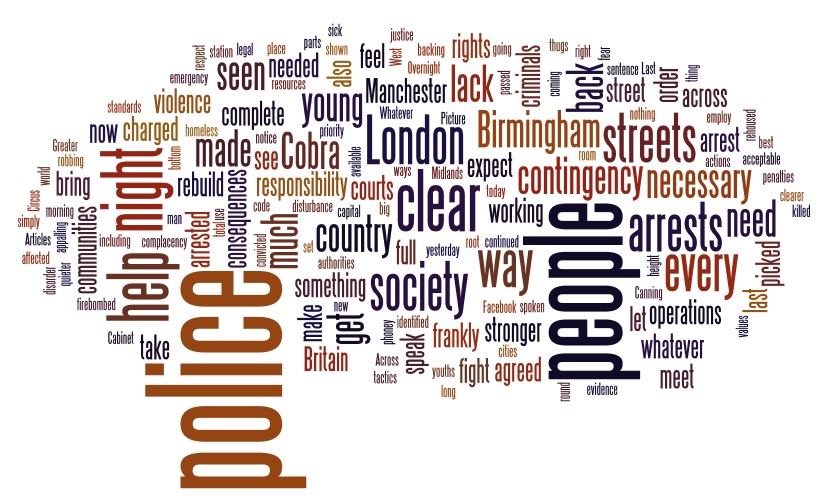

Når man skal lave en diskursanalyse på denne tekst (teksten nedenfor), kan man passende starte med at lave en wordle (http://www.wordle.net/create ), som viser i en billedfil (sat ind nedenfor) hyppigheden af forskellige ord i teksten.

Læg mærke

til, at de to hyppigst brugte ord er ”police” og

”people”. Man kan ikke altid være så heldig. Ofte vil de almindeligste

ord

kunne være forbinderord, bestemt artikel, o.lign. (Sådanne

ord kan man pille ud, når man laver

wordlen).

Men

her er to ord, som med det samme

er afslørende for den dominerende diskurs.

Det

kan beskrives som en lov-og-orden

(”police”) diskurs, og det er en inkluderende diskurs (”people”, som vi

alle må

forventes at tilhøre, bortset fra the thugs (bøllerne), der har lave al

uordenen.

En række ord støtter den

dominerende diskurs, f.eks. arrests, criminal, courts, justice,

sentence,

prison, thuggery, consequences, etc.

Det

inkluderende people-sprogelement,

der opfordrer til sammenhold imod bøllerne, indbefatter ord som

community, Britain,

etc.

''Since yesterday there are more police

on the street, more people have been arrested and more people are being

charged

and prosecuted.

Last night there were around 16,000

police on the streets of London, and there is evidence a more robust

approach

to policing in London resulted in a much quieter night across the

capital.

And let me pay tribute to the bravery of

those police officers and indeed everyone working for our emergency

services.

In total there have been 750 arrests in

London since Saturday, with more than 160 people being charged.

Today, major police operations are under

way as I speak to arrest the criminals who were not picked up last

night but

who were picked up on closed circuit television cameras.

Related Articles

Picture by picture, these criminals are

being identified, arrested and we will not let any phoney concerns

about human

rights get in the way of the publication of these pictures and arrest

of these

individuals.

As I speak, sentences are also being

passed, courts sat through the night last night and will do again

tonight.

It is for the courts to sentence but I

would expect anyone convicted of violent disorder will be sent to

prison.

We needed a fight back and a fight back

is under way.

We have seen the worst of Britain but I

also believe we have seen some of the best of Britain: the million

people who

have signed up on Facebook to support the police; communities coming

together

in the clean-up operations.

But there is absolutely no room for

complacency and there is much more to be done.

Overnight we saw the same appalling

violence and thuggery that we have seen in London in new cities,

including

Birmingham, Manchester and Nottingham.

In the West Midlands, three men were

killed in a hit-and-run in Birmingham and the police are working round

the

clock to get to the bottom of what happened and bring the perpetrator

to justice.

In Birmingham, over 160 arrests were

made.

In Salford, up to 1,000 youths were

attacking the police at the height of the disturbance.

Across Greater Manchester, more than 100

arrests were made and, in Nottinghamshire, Canning Circus police

station was firebombed

and over 80 arrests were made.

This continued violence is simply not

acceptable and it will be stopped.

We will not put up with this in our

country, we will not allow a culture of fear to exist on our streets.

Let me be clear, at Cobra this morning

we agreed full contingency planning is going ahead.

Whatever resources the police need they

will get, whatever tactics police feel they need to employ, they will

have

legal backing to do so.

We will do whatever is necessary to

restore law and order on to our streets.

Every contingency is being looked at,

nothing is off the table.

The police are already authorised to use

baton rounds and we agreed at Cobra that while they are not currently

needed,

we now have in place contingency plans for water cannon to be available

at 24

hours' notice.

It is all too clear that we have a big

problem with gangs in our country. For too long there had been a lack

of focus

on the complete lack of respect shown by these groups of thugs.

I'm clear that they are in no way

representative

of the vast majority of young people in our country who despise them,

frankly,

as much as the rest of us do.

But there are pockets of our society

that are not just broken but frankly sick.

When we see children as young as 12 and

13 looting and laughing, when we see the disgusting sight of an injured

young

man with people pretending to help him while they are robbing him, it

is clear

that there are things that are badly wrong with our society.

For me, the root cause of this mindless

selfishness is the same thing I have spoken about for years.

It is a complete lack of responsibility

in parts of our society, people allowed to feel the world owes them

something,

that their rights outweigh their responsibilities and their actions do

not have

consequences.

Well, they do have consequences.

We need to have a clearer code of

standards and values that we expect people to live by and stronger

penalties if

they cross the line.

Restoring a stronger sense of

responsibility across our society in every town, in every street, in

every

estate is something I am determined to do.

Tomorrow Cobra will meet again, Cabinet

will meet, I will make a statement to Parliament, I'll set out in full

the

measures that we will take to help businesses that have been affected,

to help

rebuild communities, to help rebuild the shops and buildings that have

been

damaged, to make sure the homeless are rehoused, to help local

authorities in

all the ways that are necessary.

But today, right now, the priority is

still clear: we will take every action necessary to bring order back to

our

streets.''

After

Riots Speech (15 August 2011)

Cameron

forholdt sig til optøjerne I en stor after riots

speech. (Nedenfor). Wordlen er vist ovenover. Og det er

interessant at se, at “PEOPLE” er det mest brugte ord. Talen indeholder

mange

af de samme elementer som den foregående, men der er nu en endnu større

understregning af sammenholdet (jvf f.eks. slutningen på talen). Den dominerende diskurs er

et velkendt

Cameron-tema, som den moderat konservative partileder allerede anslog i

valgkampen, der bragte ham til magten i 2010, nemlig ”BROKEN BRITAIN

AND HOW TO

MEND IT”. Broken

Britain er de

samfundsmæssige opløsningstendenser, som Cameron mener at se omkring

sig:

Familieopløsning, øget kriminalitet, fremmedgørelse i storbyernes

forstæder,

etc. Ordet ”moral”

har en fremtrædende

placering i ordkæderne, der understøtter den dominerende diskurs:

No, this was about behaviour...

...people showing indifference to right and wrong...

...people with a twisted moral code...

...people with a complete absence of self-restraint.

Samtidig

afvises, at regeringens welfare cuts kunne spille

en rolle.

De unge har en moralsk pligt

til at opføre sig ordentligt. Samfundsstøtterne og folket har en pligt

til at

bakke op. Det, der skete var ikke rationelt forståeligt. Det var

”sickening

acts”. Det var udtryk for en slags iboende ondskab, og derfor er det

relevant

at forholde sig moralsk til det.

I

kontrast hertil kunne man se

Labourlederen Ed Milliband holde taler, hvor han også afviste adfærden

omkring

butiskplyndringer og vold som uantagelig, men samtidig lagde op til en

slags

forståelse af mulige baggrundsårsager. Diskurserne er forskellige hos henholdsvis den moderate konservative og den moderate socialist.

Cameron-tale:

It

is time for our country to take

stock.

Last

week we saw some of the most

sickening acts on our streets.

I'll never forget talking to Maurice Reeves,

whose family had run the

Reeves furniture store in Croydon for generations.

This was an 80 year old man who had seen the

business he had loved, that

his family had built up for generations, simply destroyed.

A hundred years of hard work, burned to the

ground in a few hours.

But last week we didn't just see the worst of

the British people; we saw

the best of them too.

The ones who called themselves riot wombles and

headed down to the

hardware stores to pick up brooms and start the clean-up.

The people who linked arms together to stand

and defend their homes,

their businesses.

The policemen and women and fire officers who

worked long, hard shifts,

sleeping in corridors then going out again to put their life on the

line.

Everywhere I've been this past week, in

Salford, Manchester, Birmingham,

Croydon, people of every background, colour and religion have shared

the same

moral outrage and hurt for our country.

Because this is Britain.

This is a great country of good people.

Those thugs we saw last week do not represent

us, nor do they represent

our young people - and they will not drag us down.

But now that the fires have been put out and

the smoke has cleared, the

question hangs in the air: 'Why? How could this happen on our streets

and in

our country?'

Of course, we mustn't oversimplify.

There were different things going on in

different parts of the country.

In Tottenham some of the anger was directed at

the police.

In Salford there was some organised crime, a

calculated attack on the

forces of order.

But what we know for sure is that in large

parts of the country this was

just pure criminality.

So as we begin the necessary processes of

inquiry, investigation,

listening and learning: let's be clear.

These riots were not about race: the

perpetrators and the victims were

white, black and Asian.

These riots were not about government cuts:

they were directed at high

street stores, not Parliament.

And these riots were not about poverty: that

insults the millions of

people who, whatever the hardship, would never dream of making others

suffer

like this.

No, this was about behaviour...

...people showing indifference to right and

wrong...

...people with a twisted moral code...

...people with a complete absence of

self-restraint.

Now I know as soon as I use words like

'behaviour' and 'moral' people

will say - what gives politicians the right to lecture us?

Of course we're not perfect.

But politicians shying away from speaking the

truth about behaviour,

about morality...

...this has actually helped to cause the social

problems we see around

us.

We have been too unwilling for too long to talk

about what is right and

what is wrong.

We have too often avoided saying what needs to

be said - about

everything from

marriage to welfare to common courtesy.

Sometimes the reasons for that are noble - we

don't want to insult or

hurt people.

Sometimes they're ideological - we don't feel

it's the job of the state

to try and pass judgement on people's behaviour or engineer personal

morality.

And sometimes they're just human - we're not

perfect beings ourselves

and we don't want to look like hypocrites.

So you can't say that marriage and commitment

are good things - for fear

of alienating single mothers.

You don't deal properly with children who

repeatedly fail in school -

because you're worried about being accused of stigmatising them.

You're wary of talking about those who have

never worked and never want

to work - in case you're charged with not getting it, being middle

class and

out of touch.

In this risk-free ground of moral neutrality

there are no bad choices,

just different lifestyles.

People aren't the architects of their own

problems, they are victims of

circumstance.

'Live and let live' becomes 'do what you

please.'

Well actually, what last week has shown is that

this moral neutrality,

this relativism - it's not going to cut it any more.

One of the biggest lessons of these riots is

that we've got to talk

honestly about behaviour and then act - because bad behaviour has

literally

arrived on people's doorsteps.

And we can't shy away from the truth anymore.

So this must be a wake-up call for our country.

Social problems that have been festering for

decades have exploded in

our face.

Now, just as people last week wanted criminals

robustly confronted on

our street, so they want to see these social problems taken on and

defeated.

Our security fightback must be matched by a

social fightback.

We must fight back against the attitudes and

assumptions that have

brought parts of our society to this shocking state.

We know what's gone wrong: the question is, do

we have the determination

to put it right?

Do we have the determination to confront the

slow-motion moral collapse

that has taken place in parts of our country these past few generations?

Irresponsibility. Selfishness. Behaving as if

your choices have no

consequences.

Children without fathers. Schools without

discipline. Reward without

effort.

Crime without punishment. Rights without

responsibilities. Communities

without control.

Some of the worst aspects of human nature

tolerated, indulged -

sometimes even incentivised - by a state and its agencies that in parts

have

become literally de-moralised.

So do we have the determination to confront all

this and turn it around?

I have the very strong sense that the

responsible majority of people in

this country not only have that determination; they are crying out for

their

government to act upon it.

And I can assure you, I will not be found

wanting.

In my very first act as leader of this party I

signalled my personal

priority: to mend our broken society.

That passion is stronger today than ever.

Yes, we have had an economic crisis to deal

with, clearing up the

terrible mess we inherited, and we are not out of those woods yet - not

by a

long way.

But I repeat today, as I have on many occasions

these last few years,

that the reason I am in politics is to build a bigger, stronger society.

Stronger families. Stronger communities. A

stronger society.

This is what I came into politics to do - and

the shocking events of

last week have renewed in me that drive.

So I can announce today that over the next few

weeks, I and ministers

from across the coalition government will review every aspect of our

work to

mend our broken society...

...on schools, welfare, families, parenting,

addiction, communities...

...on the cultural, legal, bureaucratic

problems in our society too:

...from the twisting and misrepresenting of

human rights that has

undermined personal

responsibility...

...to the obsession with health and safety that

has eroded people's

willingness to act according to common sense.

We will review our work and consider whether

our plans and programmes

are big enough and bold enough to deliver the change that I feel this

country

now wants to see.

Government cannot legislate to change

behaviour, but it is wrong to

think the State is a bystander.

Because people's behaviour does not happen in a

vacuum: it is affected

by the rules government sets and how they are enforced...

...by the services government provides and how

they are delivered...

...and perhaps above all by the signals

government sends about the kinds

of behaviour

that are encouraged and rewarded.

So yes, the broken society is back at the top

of my agenda.

And as we review our policies in the weeks

ahead, today I want to set

out the priority areas I will be looking at, and give you a sense of

where I

think we need to raise our

ambitions.

First and foremost, we need a security

fight-back.

We need to reclaim our streets from the thugs

who didn't just spring out

of nowhere

last week, but who've been making lives a misery for years.

Now I know there have been questions in

people's minds about my approach

to law and order.

Well, I don't want there to be any doubt.

Nothing in this job is more important to me

than keeping people safe.

And it is obvious to me that to do that we've

got to be tough, we've got

to be robust, we've got to score a clear line between right and wrong

right

through the heart of this country - in every street and in every

community.

That starts with a stronger police presence -

pounding the beat,

deterring crime, ready to re-group and crack down at the first sign of

trouble.

Let me be clear: under this government we will

always have enough police

officers to be able to scale up our deployments in the way we saw last

week.

To those who say this means we need to abandon

our plans to make savings

in police budgets, I say you are missing the point.

The point is that what really matters in this

fight-back is the amount

of time the police actually spend on the streets.

For years we've had a police force suffocated

by bureaucracy, officers

spending the majority of their time filling in forms and stuck behind

desks.

This won't be fixed by pumping money in and

keeping things basically as

they've been.

As the Home Secretary will explain tomorrow, it

will be fixed by

completely changing the way the police work.

Scrapping the paperwork that holds them back,

getting them out on the

streets where people can see them and criminals can fear them.

Our reforms mean that the police are going to

answer directly to the

people.

You want more tough, no-nonsense policing?

You want to make sure the police spend more

time confronting the thugs

in your neighbourhood and less time meeting targets by stopping

motorists?

You want the police out patrolling your streets

instead of sitting

behind their desks?

Elected police and crime commissioners are part

of the answer: they will

provide that direct accountability so you can finally get what you want

when it

comes to policing.

The point of our police reforms is not to save

money, not to change

things for the sake of it - but to fight crime.

And in the light of last week it's clear that

we now have to go even

further, even faster in beefing up the powers and presence of the

police.

Already we've given backing to measures like

dispersal orders, we're

toughening curfew powers, we're giving police officers the power to

remove face

coverings from rioters, we're looking at giving them more powers to

confiscate

offenders' property - and over the coming months you're going to see

even more.

It's time for something else too.

A concerted, all-out war on gangs and gang

culture.

This isn't some side issue.

It is a major criminal disease that has

infected streets and estates

across our country.

Stamping out these gangs is a new national

priority.

Last week I set up a cross-government programme

to look at every aspect

of this problem.

We will fight back against gangs, crime and the

thugs who make people's

lives hell and we will fight back hard.

The last front in that fight is proper

punishment.

On the radio last week they interviewed one of

the young men who'd been

looting in Manchester.

He said he was going to carry on until he got

caught.

This will be my first arrest, he said.

The prisons were already overflowing so he'd

just get an ASBO, and he

could live with that.

Well, we've got to show him and everyone like

him that the party's over.

I know that when politicians talk about

punishment and tough sentencing

people roll their eyes.

Yes, last week we saw the criminal justice

system deal with an

unprecedented challenge: the courts sat through the night and dispensed

swift,

firm justice.

We saw that the system was on the side of the

law-abiding majority.

But confidence in the system is still too low.

And believe me - I understand the anger with

the level of crime in our

country today and I am determined we sort it out and restore people's

faith

that if someone hurts our society, if they break the rules in our

society, then

society will punish them for it.

And we will tackle the hard core of people who

persistently reoffend and

blight the lives of their communities.

So no-one should doubt this government's

determination to be tough on

crime and to mount an effective security fight-back.

But we need much more than that.

We need a social fight-back too, with big

changes right through our

society.

Let me start with families.

The question people asked over and over again

last week was 'where are

the parents?

Why aren't they keeping the rioting kids

indoors?'

Tragically that's been followed in some cases

by judges rightly

lamenting: "why don't the parents even turn up when their children are

in

court?"

Well, join the dots and you have a clear idea

about why some of these

young people

were behaving so terribly.

Either there was no one at home, they didn't

much care or they'd lost

control.

Families matter.

I don't doubt that many of the rioters out last

week have no father at

home.

Perhaps they come from one of the

neighbourhoods where it's standard for

children to have a mum and not a dad...

...where it's normal for young men to grow up

without a male role model,

looking to the streets for their father figures, filled up with rage

and anger.

So if we want to have any hope of mending our

broken society, family and

parenting is where we've got to start.

I've been saying this for years, since before I

was Prime Minister, since

before I was leader of the Conservative Party.

So: from here on I want a family test applied

to all domestic policy.

If it hurts families, if it undermines

commitment, if it tramples over

the values that keeps people together, or stops families from being

together,

then we shouldn't do it.

More than that, we've got to get out there and

make a positive

difference to the way families work, the way people bring up their

children...

...and we've got to be less sensitive to the

charge that this is about

interfering or nannying.

We are working on ways to help improve

parenting - well now I want that

work accelerated, expanded and implemented as quickly as possible.

This has got to be right at the top of our

priority list.

And we need more urgent action, too, on the

families that some people

call 'problem', others call 'troubled'.

The ones that everyone in their neighbourhood

knows and often avoids.

Last December I asked Emma Harrison to develop

a plan to help get these

families on track.

It became clear to me earlier this year that -

as can so often happen -

those plans were being held back by bureaucracy.

So even before the riots happened, I asked for

an explanation.

Now that the riots have happened I will make

sure that we clear away the

red tape and the bureaucratic wrangling, and put rocket boosters under

this

programme...

...with a clear ambition that within the

lifetime of this Parliament we

will turn around the lives of the 120,000 most troubled families in the

country.

The next part of the social fight-back is what

happens in schools.

We need an education system which reinforces

the message that if you do

the wrong thing you'll be disciplined...

...but if you work hard and play by the rules

you will succeed.

This isn't a distant dream.

It's already happening in schools like Woodside

High in Tottenham and

Mossbourne in Hackney.

They expect high standards from every child and

make no excuses for

failure to work hard.

They foster pride through strict uniform and

behaviour policies.

And they provide an alternative to street

culture by showing how anyone

can get up and get on if they apply themselves.

Kids from Hammersmith and Hackney are now going

to top universities

thanks to these schools.

We need many more like them which is why we are

creating more academies...

...why the people behind these success stories

are now opening free

schools...

...and why we have pledged to turn round the

200 weakest secondaries and

the 200

weakest primaries in the next year.

But with the failures in our education system

so deep, we can't just say

'these are our plans and we believe in them, let's sit back while they

take

effect'.

I now want us to push further, faster.

Are we really doing enough to ensure that great

new schools are set up

in the poorest

areas, to help the children who need them most?

And why are we putting up with the complete

scandal of schools being

allowed to fail, year after year?

If young people have left school without being

able to read or write,

why shouldn't that school be held more directly accountable?

Yes, these questions are already being asked

across government but what

happened last week gives them a new urgency - and we need to act on it.

Just as we want schools to be proud of we want

everyone to feel proud of

their communities.

We need a sense of social responsibility at the

heart of every

community.

Yet the truth is that for too long the big

bossy bureaucratic state has

drained it away.

It's usurped local leadership with its endless

Whitehall diktats.

It's frustrated local organisers with its rules

and regulations

And it's denied local people any real kind of

say over what goes on

where they live.

Is it any wonder that many people don't feel

they have a stake in their

community?

This has got to change. And we're already

taking steps to change it.

That's why we want executive Mayors in our

twelve biggest cities...

...because strong civic leadership can make a

real difference in

creating that sense of belonging.

We're training an army of community organisers

to work in our most

deprived neighbourhoods...

...because we're serious about encouraging

social action and giving

people a real chance to improve the community in which they live.

We're changing the planning rules and giving

people the right to take

over local assets.

But the question I want to ask now is this.

Are these changes big enough to foster the sense of belonging we want

to see?

Are these changes bold enough to spread the

social responsibility we

need right across our communities, especially in our cities?

That's what we're going to be looking at

urgently over the coming weeks.

Because we won't get things right in our

country if we don't get them

right in our communities.

But one of the biggest parts of this social

fight-back is fixing the

welfare system.

For years we've had a system that encourages

the worst in people - that

incites laziness, that excuses bad behaviour, that erodes

self-discipline, that

discourages hard work...

...above all that drains responsibility away

from people.

We talk about moral hazard in our financial

system - where banks think

they can act recklessly because the state will always bail them out...

...well this is moral hazard in our welfare

system - people thinking

they can be as irresponsible as they like because the state will always

bail

them out.

We're already addressing this through the

Welfare Reform Bill going

through parliament.

But I'm not satisfied that we're doing all we

can.

I want us to look at toughening up the

conditions for those who are out

of work and receiving benefits...

...and speeding up our efforts to get all those

who can work back to

work

Work is at the heart of a responsible society.

So getting more of our young people into jobs,

or up and running in

their own businesses is a critical part of how we strengthen

responsibility in

our society.

Our Work Programme is the first step, with

local authorities, charities,

social enterprises and businesses all working together to provide the

best

possible help to get a job.

It leaves no one behind - including those who

have been on welfare for

years.

But there is more we need to do, to boost

self-employment and

enterprise...

...because it's only by getting our young

people into work that we can

build an ownership society in which everyone feels they have a stake.

As we consider these questions of attitude and

behaviour, the signals

that government sends, and the incentives it creates...

...we inevitably come to the question of the

Human Rights Act and the

culture associated with it.

Let me be clear: in this country we are proud

to stand up for human rights,

at home and abroad. It is part of the British tradition.

But what is alien to our tradition - and now

exerting such a corrosive

influence on behaviour and morality...

...is the twisting and misrepresenting of human

rights in a way that has

undermined personal responsibility.

We are attacking this problem from both sides.

We're working to develop a way through the

morass by looking at creating

our own British Bill of Rights.

And we will be using our current chairmanship

of the Council of Europe

to seek agreement to important operational changes to the European

Convention

on Human Rights.

But this is all frustratingly slow.

The truth is, the interpretation of human

rights legislation has exerted

a chilling effect on public sector organisations, leading them to act

in ways

that fly in the face of common sense, offend our sense of right and

wrong, and

undermine responsibility.

It is exactly the same with health and safety -

where regulations have

often been twisted out of all recognition into a culture where the

words

'health and safety' are lazily trotted out to justify all sorts of

actions and

regulations that damage our social fabric.

So I want to make something very clear: I get

it. This stuff matters.

And as we urgently review the work we're doing

on the broken society,

judging whether it's ambitious enough - I want to make it clear that

there will

be no holds barred...

...and that most definitely includes the human

rights and health and

safety culture.

Many people have long thought that the answer

to these questions of

social behaviour is to bring back national service.

In many ways I agree...

...and that's why we are actually introducing

something similar -

National Citizen Service.

It's a non-military programme that captures the

spirit of national service.

It takes sixteen year-olds from different

backgrounds and gets them to

work together.

They work in their communities, whether that's

coaching children to play

football, visiting old people at the hospital or offering a bike repair

service

to the community.

It shows young people that doing good can feel

good.

The real thrill is from building things up, not

tearing them down.

Team-work, discipline, duty, decency: these

might sound old-fashioned

words but they are part of the solution to this very modern problem of

alienated, angry young

people.

Restoring those values is what National Citizen

Service is all about.

I passionately believe in this idea.

It's something we've been developing for years.

Thousands of teenagers are taking part this

summer.

The plan is for thirty thousand to take part

next year.

But in response to the riots I will say this.

This should become a great national effort.

Let's make National Citizen Service available

to all sixteen year olds

as a rite of passage.

We can do that if we work together: businesses,

charities, schools and

social enterprises...

...and in the months ahead I will put renewed

effort into making it

happen.

Today I've talked a lot about what the

government is going to do.

But let me be clear:

This social fight-back is not a job for

government on its own.

Government doesn't run the businesses that

create jobs and turn lives

around.

Government doesn't make the video games or

print the magazines or

produce the music that tells young people what's important in life.

Government can't be on every street and in

every estate, instilling the

values that matter.

This is a problem that has deep roots in our

society, and it's a job for

all of our society to help fix it.

In the highest offices, the plushest

boardrooms, the most influential

jobs, we need to think about the example we are setting.

Moral decline and bad behaviour is not limited

to a few of the poorest

parts of our society.

In the banking crisis, with MPs' expenses, in

the phone hacking scandal,

we have seen some of the worst cases of greed, irresponsibility and

entitlement.

The restoration of responsibility has to cut

right across our society.

Because whatever the arguments, we all belong

to the same society, and

we all have a stake in making it better.

There is no 'them' and 'us' - there is us.

We are all in this together, and we will mend

our broken society -

together.